Spreading understanding of leprosy through dialogue, a colony resident aims for a society without discrimination

In 2018, India detected 120,334 new cases of leprosy, accounting for roughly 60% of the global total. Although the country has achieved the World Health Organization’s target set in 2005 for the elimination of leprosy as a public health problem – a prevalence rate below one in 10,000 population – there are still areas where the disease exists, and persons affected by leprosy continue to face firmly rooted discrimination both in terms of laws and customs. Chandra Prakash Kumar is a young Indian who is working to eliminate this discrimination.

Leprosy = untouchable

In India, contracting leprosy used to mean becoming a beggar

Mr. Kumar is the child of persons affected by leprosy and was raised in a leprosy colony. He is now studying hotel management at a university in Mangalore in the Indian state of Karnataka, and also working to eliminate discrimination against persons affected by leprosy. Speaking at the 15th Global Appeal to end stigma and discrimination against persons affected by leprosy, held in Tokyo on January 27, 2020, he shared his personal experiences of the discrimination faced by persons affected by leprosy in India.

Mr. Kumar noted that there are more than 700 leprosy colonies in India, and explained that these are settlements where people who had contracted leprosy gathered after having contracted the disease and been driven out of their homes by family and neighbors. The environment is not at all pleasant; people from neighboring villages even go there to throw out their trash and unwanted items.

Colony residents generally comprise three generations – first-generation persons affected by leprosy, who have been cured of the disease but still have physical after-effects, and their children and grandchildren. Even the second- and third-generation residents have limited access to education, and the fact that they live in the colony alone can limit their possibilities for work to low-wage day labor or begging.

Mr. Kumar explains that residents become used to being discriminated against, especially those who have lived there all of their lives and know of nothing else. When people from outside the colony come, they sometimes hold their hand over their mouth and nose to avoid breathing the same air, and some people come to look at the colony as if it were a tourist attraction. People will maintain a certain distance from colony residents when walking down the street, and if residents go to a restaurant, they are served their food on a banana leaf and their drinks in plastic cups, while other diners are served using glass tableware.

Leprosy is almost never transmitted in daily life. It is also completely curable and the medicine is free, and once a person has begun treatment, they will no longer pass on the disease. Nevertheless, discrimination continues, but Mr. Kumar remains calm as he discusses these painful memories.

Eliminating discrimination through dialogue

Mr. Kumar’s life in the colony changed several years ago when the foundation Little Flower, which was established by a person who had worked with Mother Theresa and understood leprosy, came to the colony and built houses and a school.

Mr. Kumar recalls when someone from Little Flower wanted to build a road to connect the colony and a nearby village. Until then, the colony had been a final destination where people brought trash and other unwanted items, and there was no place to go from there. Residents could not go out and obtain items they needed for work or their daily lives.

Residents in the areas around the road opposed its construction, and there were even altercations in which people died, but the road was eventually built. This made it easier for residents to obtain things they needed for work and their daily lives, and people from surrounding areas stopped bringing their trash to the colony as well.

Thanks to the road, the colony now has a proper school, hospital, and other facilities. For Mr. Kumar, receiving an education in the colony meant that he was able to pursue higher education outside the colony. His new life started when he became a tutor in homes outside the colony. What he does is very simple. By thoroughly explaining leprosy, he strives to have people properly understand the disease. As a colony resident, his pay is extremely low, but he views this positively as an opportunity to eliminate discrimination.

Discrimination by society is the real “disease”

Discrimination still remains firmly entrenched, with some people not wanting to understand leprosy or equating leprosy with begging. Mr. Kumar explains that there are people in the world who want to feel superior to others, and others who, because of how they were raised, may discriminate without knowing it. This makes “dialogue” that much more important. If, by sitting down and talking together, people can begin to understand that colony residents are just like them and leprosy is just another illness like a cold, discrimination will be reduced. He therefore does not try to hide his background, but rather discusses it freely.

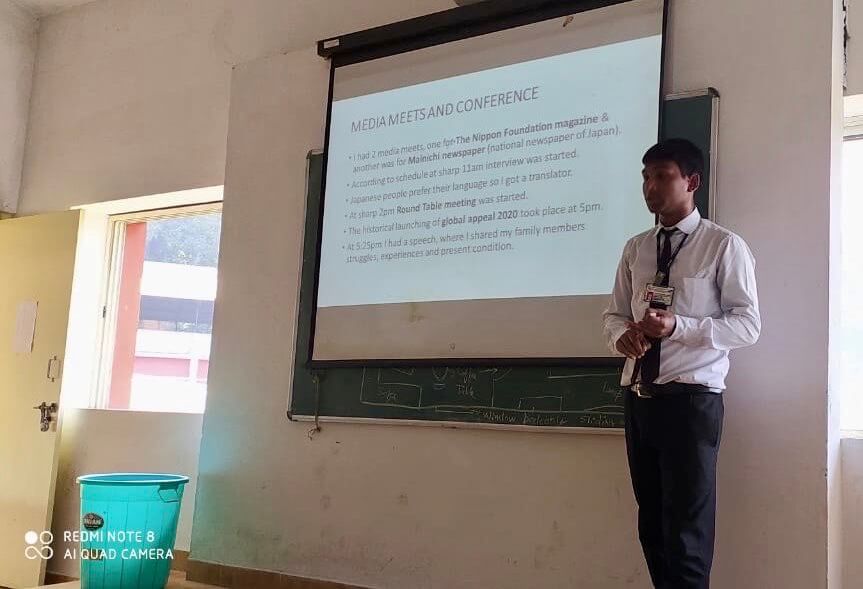

When Mr. Kumar returned to India after participating in the Global Appeal in Japan, his university asked him to give two presentations – one on basic knowledge regarding leprosy, and the other on problems related to leprosy in India. As a result, fellow students became interested in his activities and some even went with him to visit his home in the colony.

Mr. Kumar’s hope is to create a world where there is no difference between inside the colony and outside the colony. Many persons affected by leprosy have taken inspiration from his work. Their activities are sure to break down the “walls” of colonies and replace them with “roads.”

Related News

Contact

Public Relations Team

The Nippon Foundation

- Email: cc@ps.nippon-foundation.or.jp