Measures needed to implement the New VisionA 2-part report on the current situation and initiatives for the future

The Nippon Foundation has designated April 4 as Adopted Children’s Day, and around this time we hold events to promote awareness of special adoption and the situation regarding protective care in Japan. The day was chosen because the characters for April 4 can be read as yoshi, which is also the Japanese word for adoption. To mark this year’s Adopted Children’s Day, we are posting the English translation of an article written by The Nippon Foundation’s Eriko Takahashi, Program Director of Disability and Child Welfare, and published on the Japanese online site of HuffPost in October 2017. The original article was published on HuffPost’s Japanese online site in October 2017, and is available here(external site)

Unlike in the Americas and Europe, “adoption” in Japan generally means the transfer of family registry by an adult for business or inheritance-related considerations. The special childhood adoptions being promoted by The Nippon Foundation in Japan are for infants and young children who would otherwise grow up in a childcare institution, whereby they become part of an adoptive family for life, with the same legal status of children born into the family. For the purposes of this article, “adoption” refers to this special childhood adoption.

What, then, needs to be done to advance adoption and foster placement based on the concept of pursuing permanent solutions?

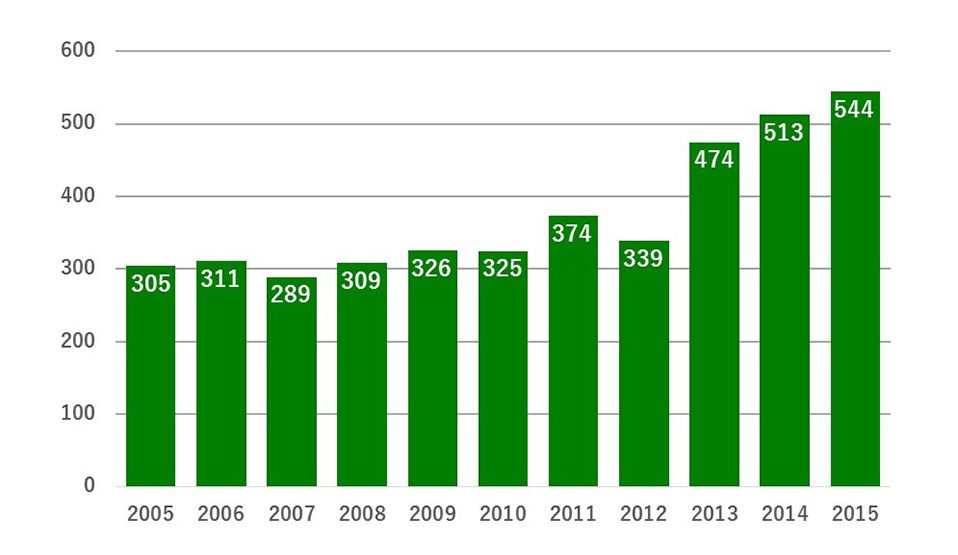

For many years, the number of adoptions in Japan hovered around 300 annually, but recent years have shown an upward trend, reaching 544 in 2015. The New Vision’s target of increasing this to 1,000 within five years does not appear out of reach.

With a rise in recent years of couples seeking infertility treatment, child guidance centers (CGCs) and independent adoption agencies have waiting lists of couples wanting to adopt infants. It is difficult to find homes for older children or children with disabilities, however, so further training and more long-term support are needed going forward.

The issue is how to arrange for the adoption of children who are not expected to be able to return to the care of their biological parents.

According to MHLW’s “Current State of Social Child Care,” there are 610 children in homes for infants who have no interaction with their parents. The first thing that needs to be done is for prefectural governments and CGCs to identify the status of relationships between children living in institutions and their biological parents, and estimate the likelihood of those children returning to live at home.

As reference, a survey carried out by the city of Fukuoka showed that 75.3% of children who lived in an institution for less than three years returned to live with their families before they turned 18, while 64.7% of children who lived in an institution for more than three years continued to live there until their 18thbirthday.

Of children who moved from homes for infants to childcare institutions (from one type of institution to another), 84.9% continued to live in the new institution. This means that: (1) It is important to work to return children in institutions to their biological parents within three years; (2) Children who are likely to remain in an institution for more than three years need to be placed into adoption or foster care at an early date; and (3) Children in homes for infants who are not returned to their biological parents are likely to remain in institutions for a long time. It would be useful if other local governments carried out similar surveys to understand their own situation.

Another MHLW survey showed that of 298 cases in which adoption should have been considered, in 68.8% of cases it was not considered because of the requirement for biological parents’ consent, and in 15.4% because of the (upper) age limit.

Revisions to the Civil Code required to resolve issues under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) are also moving forward. These changes will remove the current upper age limit of under six years old and limit the time period during which the biological father and mother can withdraw their consent, and also address whether or not directors of CGCs can initiate the adoption process on behalf of persons wanting to be adoptive parents when the parent cannot be found or is incapable of giving consent, or the welfare of the child requires that consent be dispensed with. We hope that these issues, all of which are essential for guaranteeing permanency, are resolved quickly.

Over the past few years, adoptions arranged by independent adoption agencies have accounted for roughly one-third of all successful adoptions, and these activities are also attracting attention. A law to regulate private, independent adoption agencies is scheduled to be enacted in April 2018, and we expect this to require the quality of independent agencies to improve and to strengthen public financial assistance. This will also mean that CGCs will need to change their way of thinking, and that training and regulations for implementation will be needed.

From 2017, MHLW also began creating posters and carrying out other activities to promote awareness of adoption, and these efforts are seen growing in the future.

Many Useful Overseas Examples

With regard to foster care, the New Vision calls for 75% of children under the age of three to be placed in foster care within five years, and for 75% of preschool children over the age of three to be placed within seven years.

The most recent figures put Japan’s foster care placement rate at around 18%, which might suggest that these targets are too ambitions. The city of Shizuoka, however, has raised its rate to 46%, showing that higher rates are possible under the current framework if local governments make the effort.

Naturally, raising the foster care placement rate means that prospective foster parents need to be recruited, trained, and assessed, with follow-up, making independent fostering agencies essential.

Currently, there are only a few independent fostering agencies in Japan – one being the international nonprofit agency Key Assets, which operates in Osaka and Fukuoka. The New Vision aims to establish fostering agencies in each prefecture by fiscal 2020.

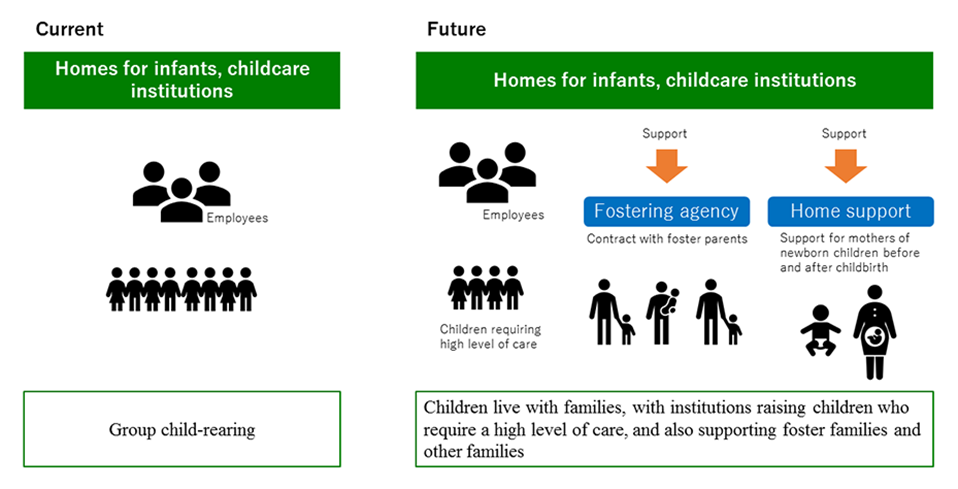

To date, children in homes for infants and childcare institutions have been raised by staff in groups, but going forward a higher level of care is needed, with children being raised by foster parents, and institutions supporting foster parents and mothers of newborn children before and after childbirth. The New Vision also aims to shift and diversify functions by providing institutions with more in-depth specialist care (see diagram).

Many staff members at homes for infants and childcare institutions are childcare professionals with high levels of expertise, and going forward they will be asked to take on new roles like becoming foster parents themselves and supporting foster parents.

The functional shift and diversification of homes for infants and childcare institutions has been underway in Britain for 30 years, and at a seminar titled “Toward a Society Where Children Are Raised at Home,” sponsored by The Nippon Foundation and held at the Japanese Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect in 2016, Sir Roger Singleton, former CEO of the British children’s charity Barnardo’s, shared his experiences with this process.

Similar movements are underway in Eastern European countries including Romania, the Czech Republic, and Bulgaria, and in Asia, Cambodia has announced an action plan to reduce the number of children placed in institutions in five provinces by 30% from the 2016 level by 2018. The move to raise children with families can be seen becoming the international norm, are there are many cases from which Japan can learn.

For the future of children

Next, let us examine the issues the New Vision needs to address if it is to move forward. One of the main reasons for the slow growth of foster care in Japan has been insufficient funding for independent adoption agencies and fostering agencies.

Going forward, the establishment of a structure for sufficient budget allocation to fostering agencies and mother-child support activities will need to be addressed urgently for the transfer of functions of homes for infants and other institutions.

In general, the cost per child in foster care is lower than for institutional care, so if foster care grows that difference will offset a corresponding amount of the overall cost of social childcare. Those funds could go to institutions supporting foster care and to institutional care, thereby strengthening the overall system.

Another issue is that CGCs are already fully occupied dealing with child abuse. As the New Vision suggests, the highest priority needs to be given to strengthening CGCs.

At the same time, simply increasing the number of foster care placements and adoptions will not necessarily improve the lives of the children involved. To achieve that, an inspection organization needs to be established quickly to evaluate all organizations involved in social childcare.

The New Vision has received much media attention, which has sparked discussion among parties involved. Nevertheless, we have not seen any particularly novel ideas put forth for family-based care at the national level. The national government has not made a significantly drastic policy change; the New Vision basically lays out targets for faster, more comprehensive, progress.

While the pursuit of numerical targets should not be carried out in a way that takes priority over children’s wellbeing, no one would oppose children being raised in a warm family atmosphere.

The importance of the first three years of a child’s life is completely different from that of three years in the life of an adult. Considering this, it is essential that we strive to provide an optimal environment for raising young children as quickly as possible.

Doing what is immediately possible can be seen as the necessary first step toward achieving the New Vision. The Nippon Foundation is holding events to coincide with Adopted Children’s Day. We hope that these events will help to instill the importance of foster care and adoption, for the sake of Japanese children’s future.

Related Link

Contact

Communications Department

The Nippon Foundation

- E-mail:cc@ps.nippon-foundation.or.jp