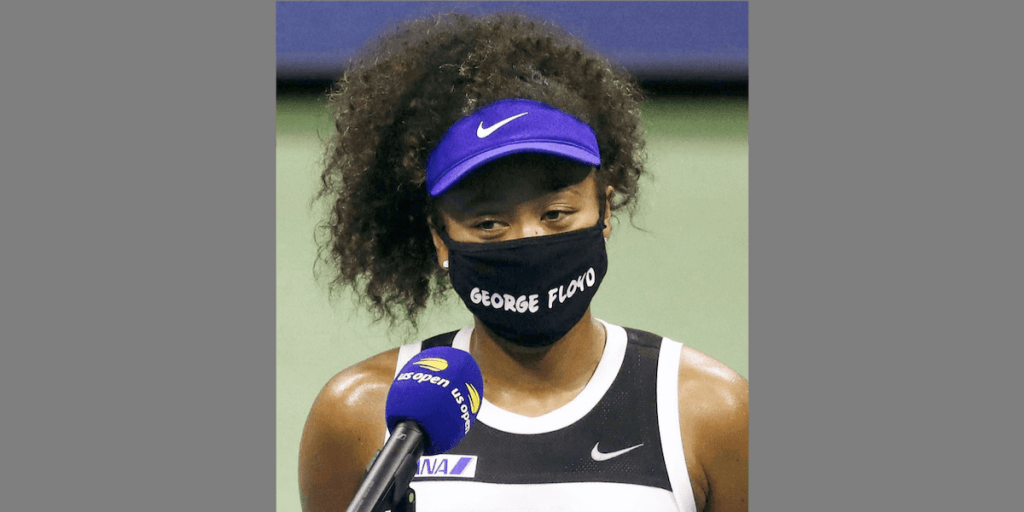

Black Power Salute“Before I am an athlete, I am a Black woman” – Naomi Osaka’s protest

Tennis player Naomi Osaka posted this statement on Twitter on August 26 after reaching the semi-final stage of the Western & Southern Open, considered a warm-up tournament for the US Open, a Grand Slam tennis tournament. This protest was in response to the shooting three days prior of a Black man by a white police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in the United States. Indicating the anguish she felt, she added, “And as a Black woman I feel as though there are much more important matters at hand that need immediate attention, rather than watching me play tennis.”

Tournament organizers immediately postponed the next day’s scheduled matches, and when play resumed the following day Ms. Osaka played and also won her match.

This followed the news in May of the death of a Black man at the hands of white police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota in the United States, which spread rapidly by social media and sent shock waves that led to demonstrations around the world.

At the same time as Ms. Osaka was taking her stand, the Milwaukee (Wisconsin) Bucks of the National Basketball Association boycotted their next scheduled game. After consulting with the players union, the NBA announced a postponement of the next scheduled game of three playoff series then underway, and Major League Baseball postponed several games as well.

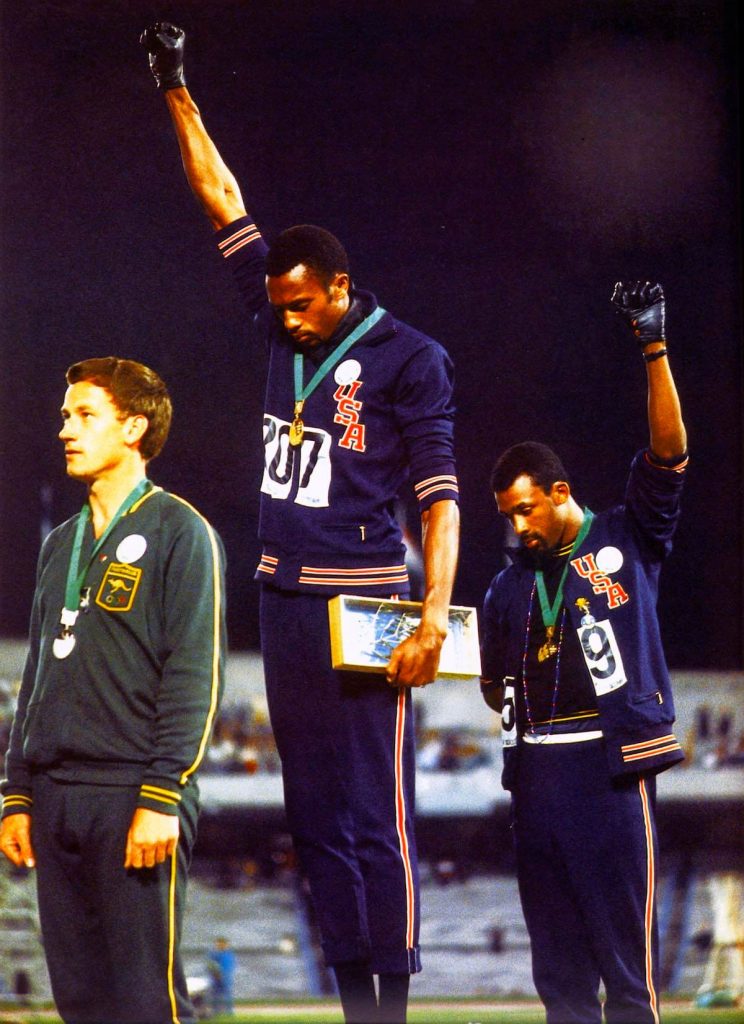

Protests against discrimination in Olympic history

Olympic history also includes well-known protests against racial discrimination. One occurred on October 16, 1968, at the awards ceremony for the Men’s 200-meter track event at the Mexico City Games. African-American athletes Tommie Smith, who won the event with a world record time of 19.83 seconds, and third-place finisher John Carlos stepped onto the podium wearing black socks and no shoes. Around their necks, Mr. Smith wore a black scarf and Mr. Carlos a string of beads in memory of those who had been lynched by white supremacists, and Mr. Smith wore a glove on his right hand and Mr. Carlos a glove on his left hand.

The medals were awarded and the U.S. national anthem was played as the U.S. flag was unfurled. In what would normally be a moment of great pride, however, the two athletes looked down and bowed their heads with their fists in black gloves raised.

The United States has a long history of racial discrimination, with people of color being denied service by hotels and restaurants, with separated seating on buses and in movie theaters, and “whites-only” public rest rooms. The movement started by Black leaders including the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. finally culminated in the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, the same year that Tokyo hosted the Summer Olympics, guaranteeing people of color the right to vote and prohibiting discrimination in public facilities.

Nevertheless, this did not mean that discrimination ended. Violence, including arson, against Black people continued, and on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated. His killing was followed by the assassination of Robert Kennedy, a candidate for president who advocated for equal rights, on June 6. Anger among Black Americans was therefore seething when the Mexico City Olympics took place later that year.

Mr. Smith and Mr. Carlos felt that they had no choice but to bring the feelings of Black Americans to the world’s attention, even though they knew that they would be sanctioned because political demonstrations and statements were prohibited at the Olympics.

As expected, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) reacted immediately. The two U.S. athletes were suspended from the Olympic team and expelled from the Olympic Village. After initially opposing the punishment, the U.S. Olympic Committee accepted the decision and forced the two to return to the United States the following day.

Afterward they said, “We are Black and we are proud of being Black. Black America will understand what we did tonight.” They received much criticism, and were ostracized by the sporting world for some time. They lost their jobs and fell into poverty, and the criticism even took a toll on their families, with Mr. Carlos’s wife committing suicide. Their reputations finally began to recover in the mid-1970s as heroes in the fight against racial discrimination. San Jose State University, their alma mater, erected a statue of the pair in their honor, but there is no question that their lives were difficult. This episode later became known as the Black Power Salute.

Peter Norman’s fate

There was a third athlete on the podium that day – Peter Norman of Australia. Hearing in advance what Mr. Smith and Mr. Carlos were planning, he decided to show his support by wearing a badge for the Olympic Project for Human Rights together with the other two. As they approached the podium, Mr. Carlos realized that he had forgotten his gloves, and it was Mr. Norman who suggested that they share the pair they had. Until a few years prior, Australia had a “White Australia Policy” that he opposed in the belief that all people are equal and the color of their skin does not matter. This stance also took a great deal of courage.

Instead of being praised as Australia’s first medalist in an Olympic sprint event, Mr. Norman also came in for criticism. He was ostracized by the sports world, lost his job, and was divorced. Despite this disappointment, he continued to compete as an athlete but never returned to the Olympic stage, and died on October 3, 2006, after a difficult life. Unlike the two Americans, who were pallbearers at his funeral, his reputation did not recover during his lifetime. After his death, the Australian government finally issued an apology to his mother in August 2012.

A dagger to the IOC

It can also be said that the Olympics have a hidden history of discrimination – racial, sexual, religious, and political. The Olympic Charter says there will be no discrimination, but also prohibits political demonstrations at Olympic venues. In January 2020, the IOC Athletes’ Commission issued guidance on Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which prohibits any kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda in any Olympic sites, venues, or other areas. This guidance prohibits kneeling during the playing of the national anthem as a form of protest against racial injustice.

The protests surrounding the recent killings of Black men in the United States are what triggered this discussion of Rule 50. In the United States, kneeling during the playing of the national anthem has spread as a form of protest against racial discrimination, especially in the National Football League. How will the IOC respond if something similar happens at the Tokyo 2020 Games? The organizing committee also needs to prepare a clear response.

Naomi Osaka and other athletes including baseball and football players have thrust a dagger into the IOC and U.S. society. The question is how they will respond, and what improvements will be made. This will have a major bearing on the Tokyo Games.

Contact

Public Relations Team

The Nippon Foundation

- Email: cc@ps.nippon-foundation.or.jp