THE TOKYO TOILET – Creators discuss their thoughts on each public toilet

The following is the first of a series of discussions with the creators involved in THE TOKYO TOILET project, being carried out by The Nippon Foundation and the Shibuya City government to renovate 17 public toilets in Shibuya to make them accessible for everyone regardless of gender, age, or disability.

Designer: Masamichi Katayama

Location: Ebisu Park

One of the things I realized when I joined The TOKYO TOILET project is that I have almost never used public toilets, and especially public toilets in parks. It may have been coincidence to some extent that I didn’t need to use them, but I thought it was unfortunate that I could not think of any that I would want to use.

All of the interior projects like stores and offices that I have been involved with to date have toilets. In those cases, the toilets’ design is based on the identity of the location and space, but we always put a great deal of attention into ease of use and privacy, in addition to simply the design.

My first consideration was that Ebisu Park is next to a kindergarten and elementary school, and is used by adults and children of all ages and all genders. I had a strong sense of wanting the facility to feel like it is a part of the park, and wanted it to fit in naturally with the park’s trees and shrubs.

As I have said before, the concept is a “modern kawaya,”* and I chose materials that would give a sense of being simple and primitive. Specifically, the concrete panels were molded to have a “wood grain” to make it appear natural and give the hard material a sense of softness.

Even though the 15 concrete panels are arranged in a way that intuitively looks simple, we made detailed calculations based on line of sight and line of flow. The indirect light that enters where the walls are joined presents the toilet as an object. Of course, there is also functional lighting for the benefit of users.

- * Kawaya were huts built over rivers that were used as toilets in Japan dating back to the prehistoric Jomon period.

Designer: Shigeru Ban

Locations: Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park

Haru-no-Ogawa Community Park

There are two concerns with public toilets located in parks – whether they are clean inside and whether there is anyone hiding inside. These glass “transparent toilets” were designed to resolve both of these issues.

The technology for making the glass become transparent when electricity passes through it was not developed for these toilets. I have used it in my previous work, for example for room partitions in the Swatch-Omega Cité du Temps in Switzerland, which was completed in 2019.

When I designed these toilets, I paid particular attention to the layout of the equipment so that it can be seen from outside when the toilet is not in use and the glass is transparent. Because they are permanent fixtures in the parks, the equipment needed to be arranged to fit in beautifully as part of the scenery.

These transparent toilets were installed in two locations, the Haru-no-Ogawa Community Park in Yoyogi and the Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park in Tomigaya. The basic structure and equipment are the same, with no common area but an individual universal toilet, women’s toilet, and men’s toilet arranged in a row. I did not want the colors to be bound to the standard red for women and blue for men, so I used a cooler color scheme in Haru-no-Ogawa Community Park and a warmer color scheme in Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park, with the aim of making them appear bright even in natural daylight.

Designer: Nao Tamura

Location: Higashi Sanchome

When I first saw the location, I thought of a small triangular “gap” in the middle of the city, sandwiched between a large concrete wall bordering the railway line in the background, with an emergency storehouse and power switching box on either side, along a road with heavy traffic.

For this small, triangular space, I drew my inspiration from origata, a traditional Japanese method for folding paper that is also the foundation of origami, and decided to create a geometric space that resembles folded paper.

Presenting a gift wrapped in folded paper is said to be pure and courteous, conveying a feeling of respect for the recipient. I wanted the toilet to be a place that is also pure and courteous, with mutual respect. To make the space feel like origata, I used thin metal plates that look like folded paper for the walls and ceiling, doing my best to avoid a sense of physical thickness.

It was not difficult to use metal plates, but the heatproofing material was somewhat whitish, and I worked hard to create the vibrant red color that I wanted for the exterior.

Red is a color that clearly conveys the location of the toilet in a confusing environment, and also alerts people who might be experiencing mental stress. I’m sure many people can remember feeling fear or stress when using a public toilet at night or when there are no people around. Unfortunately, toilets are also places where crimes are committed. Safety and privacy are the most important considerations for a public toilet. I hope that this red color will prevent impulsive crimes and give the people who use it peace of mind

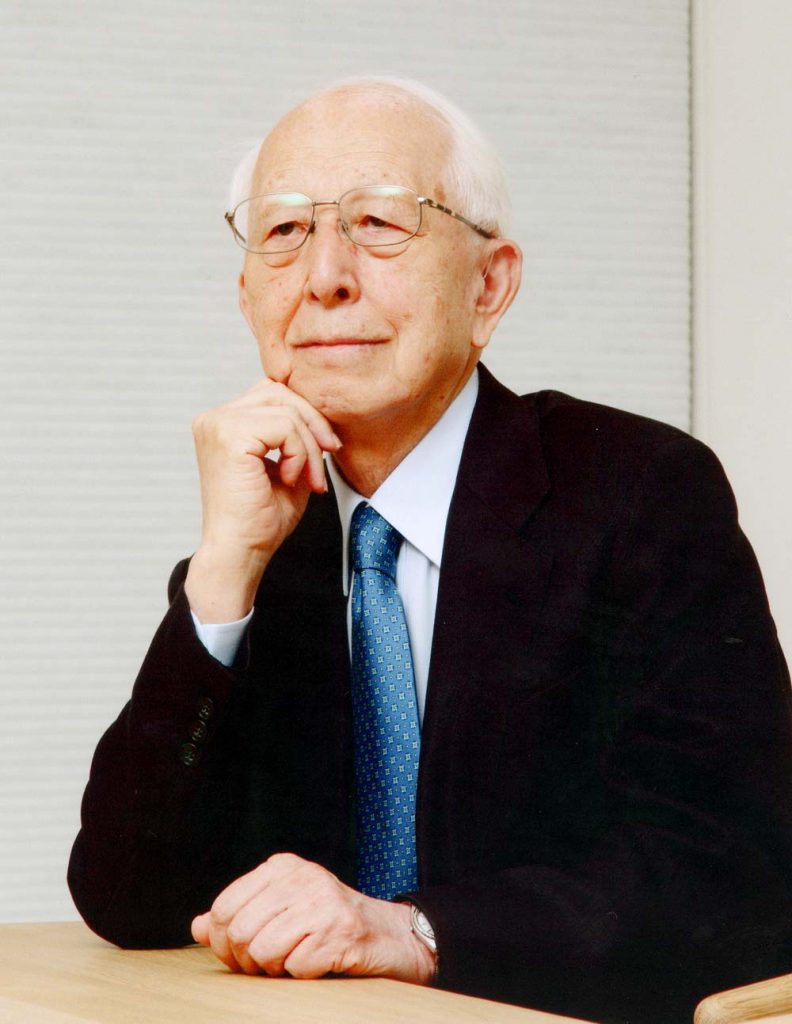

Designer: Fumihiko Maki

Location: Ebisu East Park

One of the things I try to emphasize in my design is a sense of place. This means the location’s historical background and universal value. Because this toilet is located in a park for children that has been loved for a long time by local residents, I wanted the design to be fresh and somewhat humorous.

By fresh, I mean open and bright with a hygienic environment, and humorous means a place where people using the toilet can relax and unwind. Taking into consideration things like ventilation and sunlight and users’ safety, I arranged separate rooms connected by a roof along a gentle curve. There is also a courtyard in the center that blends with the park’s lush greenery, and I have placed a bench outside the universal toilet for people to sit on and rest. I was happy to learn that many people in the park, including those not even using the toilet, enjoy sitting on this bench. From the beginning, we also incorporated the idea of the facility as a public space that serves as a park pavilion equipped with a rest area.

I also think it is important for people to know that there are ways to use locations and create public spaces that make people happy, like we have done in Ebisu East Park.

Architecture is something that remains in place for a very long time. For that reason, I want it to be a social asset for a long time. This also means that it is “decent,” and will not become embarrassing over the months and years. I hope that I have incorporated these ideas in a new way.

Designer: Takenosuke Sakakura

Location: Nishihara Itchome Park

When we first visited Nishihara Itchome Park it had a very unique atmosphere that gave an impression of being dark and lonely, so the starting point for the project was to create a public toilet as an andon (traditional Japanese lantern) to light up the park. To make the toilet a useful andon for many people, we did not emphasize the existence of the building, but instead focused on achieving as much brightness as possible. The simple, rectangular shape is how we achieved this.

Another consideration was to make the space inside the toilet feel pleasant to use. As an architect, I have designed many houses and many toilets along with them. Even though the space is limited, this is an essential place in people’s daily lives, and I always keep in mind that fact that it should not feel like a confined space that is unpleasant to use. In designing this public toilet, I wanted to create a place that feels open and as bright as possible within a limited space. This is why it has a high ceiling, while the transparent glass of the outer walls reflects the surrounding trees. The interior feels refreshing, with the sunlight filtering through the trees to illuminate a carefree space.

Including the universal toilet, there are three individual rooms that can be used by men and women. The park itself is not large, so I felt that rather than increase the number of individual rooms, it was important to have a minimum number of rooms but to design each one very carefully. There is no common area, either. I hope that as the trees planted along the path in front of the structure grow, the area will come to feel even more pleasant.

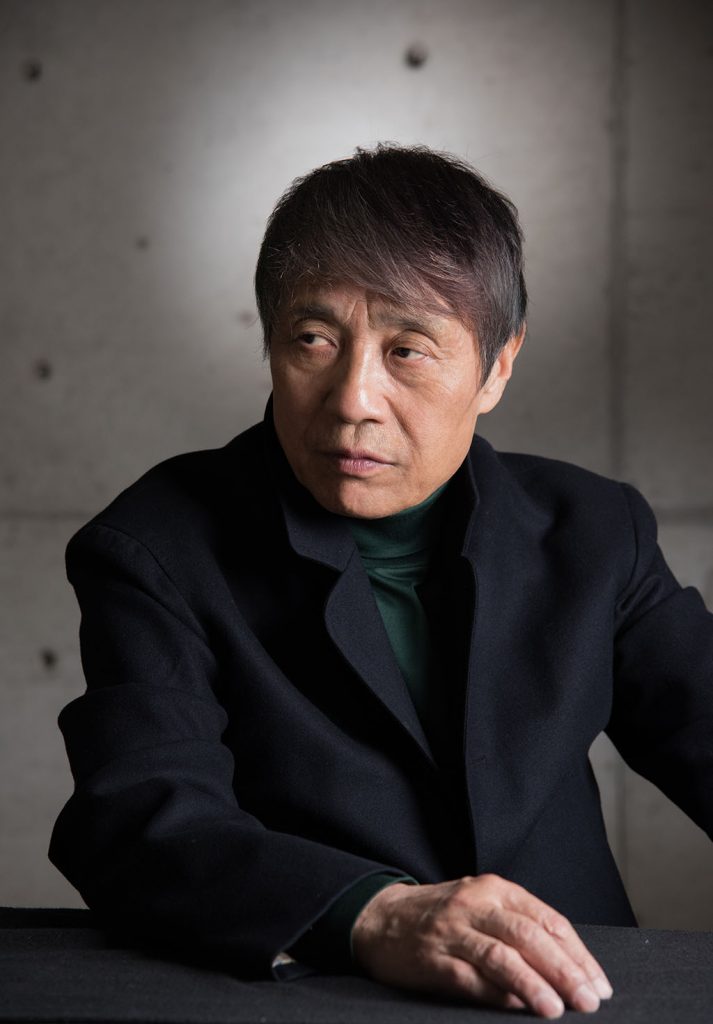

Designer: Tadao Ando

Location: Jingu-Dori Park

Japan is world renowned for its beauty, cleanliness, and courtesy, and its toilets are one of the things that embody those qualities. In my travels around the world, I have never experienced toilets that give a sense of beauty, hygiene, and a feeling of respect toward the user to the extent of toilets in Japan.

Natural ventilation is an important factor related to this beauty and cleanliness. Because of Japan’s high humidity, ventilation has been taken into consideration when designing buildings since ancient times. The deep eaves and external corridors in the traditional architecture of both houses and temples are designed for ventilation. At the same time, today ventilation is said to be one of the keys to the prevention of infectious disease. Looking at the past and considering society going forward, I would say that toilets that are bright, well ventilated, and safe are what should be sought in public toilets.

For the Jingu-Dori Park Toilet, I used a cylindrical wall of vertical louvers on the exterior of a round building to give the interior sunlight and ventilation. A circle is a fundamental shape, which I thought was appropriate for a facility that can be used freely by anyone.

The large, protruding eaves are as per my original concept of creating a toilet where people could escape to and keep dry when it rains. I have worked on many architectural projects, but this was the first time I have designed a stand-alone toilet. I hope this building will function not only as a toilet, but also as a place where people can take refuge when they have a problem, and that it will be a place that has value for everyone.

Designer: NIGO®

Location: Jingumae

The Jingumae 1-chome intersection is my favorite intersection in Tokyo. It is close to shops and a curry restaurant that I used to pass every day, so I am very happy to be involved in designing a public toilet in this location with which I feel a close connection.

The design comes from the Washington Heights Dependent Housing Area (housing for the families of U.S. military personnel) that was built in 1946 in the area that is now Yoyogi Park. Washington Heights is the place that launched the development of Harajuku into the culture town that it is today, and the Dependent Housing Area had a major effect on postwar lifestyle changes.

Almost all of the houses are now gone. I was raised in Harajuku, and that is where I am now. The concept of the toilet is to develop new things by studying the past, and I thought I would try to design a duplicate of a dependent house to preserve this disappearing design in Harajuku, an area I love.

The building looks like a welcoming house, so that it will be a public toilet that people feel comfortable using. We achieved this by paying attention to small details, like doors that open inward so they always look open, and a fence that looks like a simple garden fence.

I was careful to include hygiene in the design, so I created a large sink area and contactless faucets and fittings. I also believe a public toilet is a place where people help each other. I hope that it will stay beautiful and clean forever, and that people will use it with this in mind.

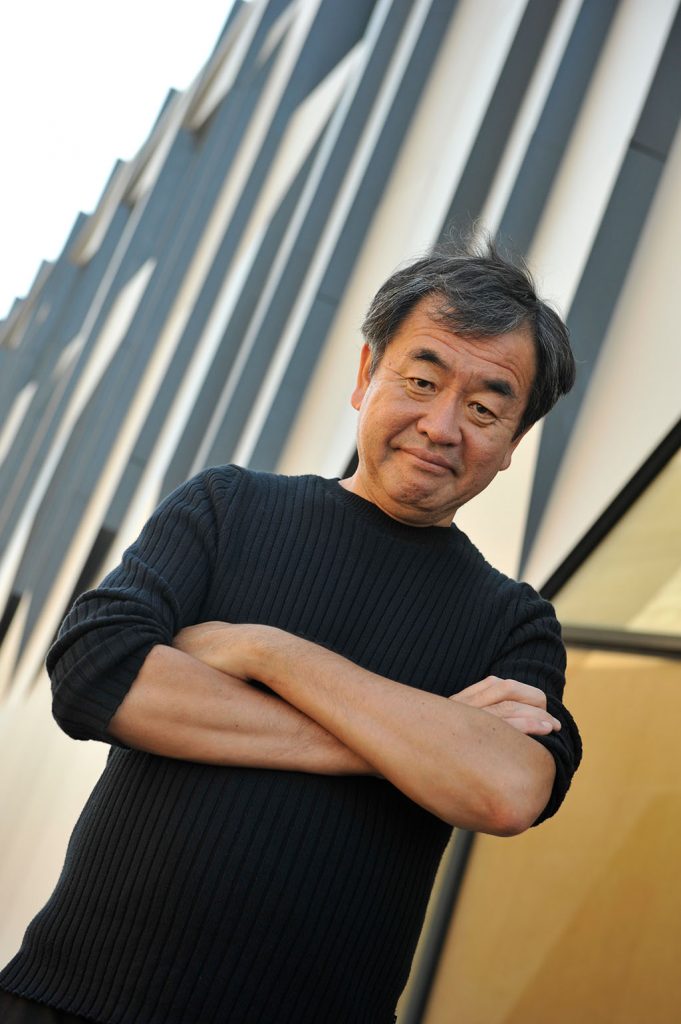

Designer: Kengo Kuma

Location: Nabeshima Shoto Park

Nabeshima Shoto Park has a pond and lush greenery, and I wanted to create a public toilet that melts into the forest. Therefore, instead of having one large box-like building, we scattered five different toilet huts and connected them with a “forest path.”

The exteriors of the huts are covered with eared cedar board louvers installed at random angles. The cedar is Yoshino cedar from Nara Prefecture, trees that have very dense rings. We used ears to create a rough feeling of being in a forest.

We used wood to bring nature back into the city. Even for a public structure like this, wood can be used in many ways depending on how it is used. Fundamentally, we wanted to convey Japan’s culture of trees to the world. The wood used for the interior decoration is Japanese cherry and zelkova and other materials from the Tsukui woods in Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture, using scraps left over from making the tops of school desks. The five toilets each have different functions and interiors, representing an age of diversity.

To make the pathway connecting the huts feel like a natural mountain path, we designed it to run along the existing slope of the park. I believe that buildings in the future will increasingly stress the relationship with their surroundings and with human emotion to create a total experience. I hope that people will use the toilet that they like, as if they were walking through nature and found it in a spot that appealed to them.

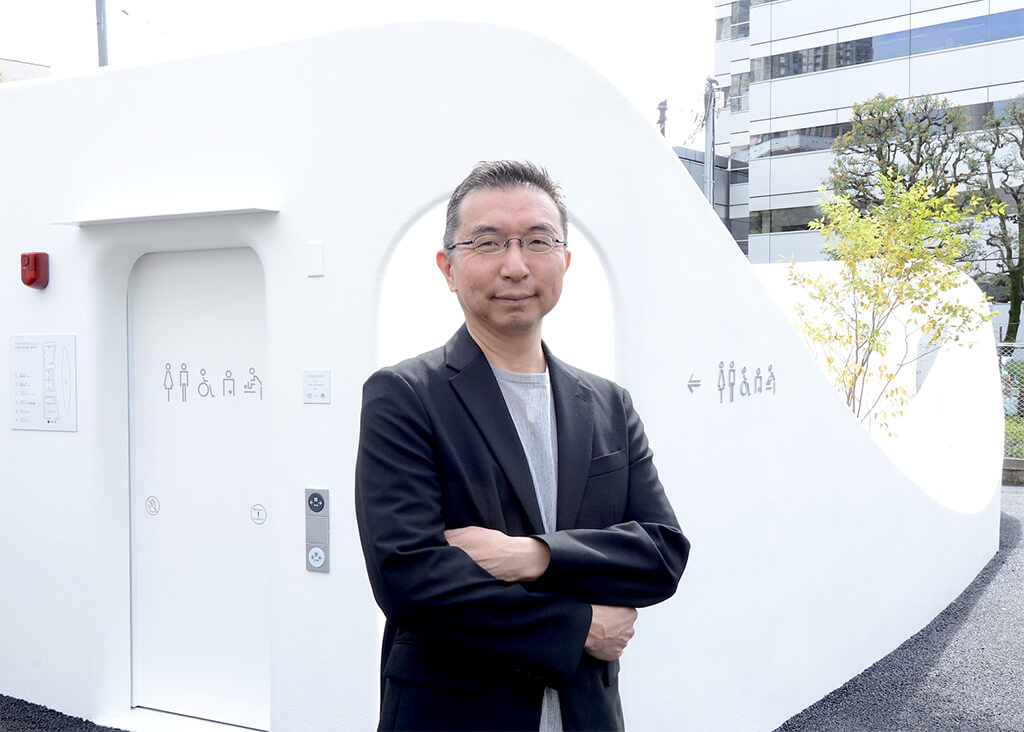

Designer: Kashiwa Sato

Location: Ebisu Station, West Exit

When we visited THE TOKYO TOILET facilities that had already been completed, we saw that they all embodied different qualities depending on their locations in places like in a park or along a major road. We used white exactly because it is different.

Treating the project as one with the main objectives of cleanliness, safety, harmony, and a society that embraces diversity, we thought about what kind of public toilet should be built next to a train and subway station. We began the design by first identifying the overall purpose and the unique aspects of the location.

The West Exit of Ebisu Station is a place that many people walk past, and the nearby statue of Ebisu (one of the Seven Deities of Good Fortune) is a popular meeting place. The location can be called the face of the neighborhood, and people who use the station to commute will see the building every day. For that reason, we thought that rather than being conspicuous as a toilet, it was more important to make it “not too conspicuous.”

It has an unobtrusive appearance that people will not notice, in a good way. We chose white to convey a sense of cleanliness, and also thought that at the same time, this would make it appear refreshing and help to brighten up the atmosphere outside the station. The louvres are designed to give peace of mind in two ways – by maintaining privacy and providing good external visibility. This also provides good ventilation, and gives an overall impression of lightness.

We paid attention to individual details that go without saying for a public toilet that is clean and easy to use, while also seeking to strike the right balance of newness without feeling out of place. We hope that the people who use it will feel comfortable and refreshed when using the toilet.

Designer: Toyo Ito

Location: Yoyogi-Hachiman

The previous toilet on this triangular lot in front of the Yoyogi-Hachiman forest gave an impression of being dark and difficult to enter. I therefore thought that the first consideration should be to make a public toilet that is bright and inviting, so that women in particular could use it at night with peace of mind. Having three separate toilet buildings makes it easy to navigate, and with no dead ends provides a line of sight that discourages crime. In addition, all three units are equipped with the functions that are normally found in universal toilets to accommodate children and older persons, so the facility can accommodate diverse needs.

The shape of the buildings, with a circular interior and round ceiling that seems to float overhead, looks like mushrooms. Initially, however, I didn’t intend for them to be mushrooms. I thought that I wanted to make them look like they sprouted up from the ground. The gradation in the mosaic tiles from dark brown to off-white transmits the land’s energy to the buildings and feels like it keeps going upward into the sky.

When I design public buildings, I try to make them fit into their natural environment as much as possible. I don’t want it to feel like a place that is disconnected from its surroundings, but rather a space where users can relax without feeling nervous. These toilets that look like mushrooms are in harmony with the Yoyogi-Hachiman forest, and I hope that local residents including children will enjoy using them.

Designer: Kazoo Sato

Location: Nanago Dori Park

My goal was to create the world’s most hygienic public toilet. To achieve this, we decided on a voice-command format for a toilet that can be used without using your hands. Research on the use of public toilets overseas shows that roughly 60% of people use their foot to push the lever to flush, roughly 50% use toilet paper when they open the door, roughly 40% close the door with their hip, and roughly 30% use their elbows to avoid hand contact. The facility was designed as a new universal experience (UX) with an “I don’t want to touch anything” mentality.

For example, if you speak the instructions for necessary operations when using the toilet, like “Open the door” or “Flush the toilet,” the task will be performed without touching anything. The system works in two languages – Japanese and English. You can also request preprogrammed music to relax your bowels. And of course, you can open the door and operate the toilet in the conventional way, using your hands, in addition to voice instructions.

After researching the needs and users of a toilet in this location, we decided to make two units – a universal toilet and a men’s toilet. The structure is a pure white globe with a ceiling that reaches four meters high at its highest, to create a fresh image that looks like a drop of water that has fallen. It was very difficult to make a spherical shape with a concrete structure, but the sphere controls the ventilation and prevents odors from stagnating, and we have installed a 24-hour ventilation system that combines a natural air supply with machine-driven exhaust.

Designer: Tomohito Ushiro

Location: Hiroo East Park

I have been involved with THE TOKYO TOILET project since the conceptual stage, and it has been more than four years since I was put in charge of this location. When the Hiroo East Park Toilet was finally completed, some people said that it looks like a small art museum, which gave me a sense of relief. The location is along a tree-lined road that leads to the Hiroo Garden Hills apartment complex, with the University of the Sacred Heart campus in the background. I approached the project with a constant sense of responsibility, aware that it would be part of the daily lives of the people who use it, including people who have lived in the area for a long time.

I began by thinking about how to make people like the toilet and feel that it is important. I wanted more than for people to like the toilet because it is clean, and tried to use a framework and create a new relationship that proactively draws people to the toilet itself.

People like public art and consider it to be important. Some people may make a toilet dirty, but few people are as careless with public art. I therefore decided to make it both public art and a public toilet.

Then I thought about how to express the objective of an art-toilet hybrid. Ultimately, I decided to use 7.9 billion lighting patterns, the same number as the world’s population, to express the project’s underlying concept of “All people are the same, in the sense that they are all different.” I also wanted to utilize the park’s lush green location, with beautiful sunlight and moonlight filtering through the trees.

Each lighting pattern is projected for only 10 seconds, and then over the next 15 seconds slowly changes to the next pattern. This uses the latest technology, but the theme is universal and the patterns can be viewed in many various ways. I hope that the changes people see every day as they walk along this tree-lined street in their daily lives will become a kind of gentle communication with the toilet.

Designer: Marc Newson

Location: Urasando

I think this is a marvelous project. I’m sure that for many people – Japanese as well as non-Japanese – this will be the first time they want to use a public toilet. There may even be people who visit THE TOKYO TOILET because they want to learn more about the culture of architecture and design. In addition to raising the status of public toilets, I believe this is also a very significant project for Shibuya.

The conditions imposed by the location of the Urasando public toilet were complex. The topography is uneven, and the Shuto Expressway runs overhead. It is also next to a public bicycle parking lot, meaning there are numerous physical limitations to take into account, and overcoming these limitations was an important process in the design.

I approached the internal space with the idea of a product rather than a structure. The need to have all functions within a relatively small space, and for it to be used for a limited but clear purpose is actually similar to a product. The concentration of technological elements in the space of a public toilet is also similar to industrial design. I have designed many aircraft cabins, and the design of a public toilet is in some ways similar to that of an aircraft cabin.

The copper Minoko roof and other elements described in the concept reference traditional Japanese architecture, which through my close relationship with Japan over many years and the projects I have been involved with in Japan, has given me great inspiration. The copper roof is one of the artisanal techniques I have often admired in Japan. I used this because I wanted to create a place that will become more attractive as it ages with the passing of time. The character will be enhanced as it gets older, and after a long time, it will look like a small monument. Similarly, the stone wall references traditional exterior architecture, and I think that eventually it will integrate extremely well with the interior’s industrial design.

Regarding the exterior materials, I consider concrete to be a typically Japanese material. Concrete is used in a very refined way in Japan today. In buildings around town, it is used with wonderful qualities. This is unique to Japan compared with other countries, and is ideal. The main structure is concrete to create a permanent space in this location while it will also melt into its surroundings, and I believe it is a material that will become a part of Japan’s contemporary landscape.

I would say that today, a project like THE TOKYO TOILET can only happen in Tokyo, in Japan. It is extremely rare for landowners, local governments, and private sector organizations and companies to work together to create a team for long-term leadership of a project to improve public toilets, and I hope this will become a reference point for other cities going forward. I hope that the people who use this toilet will find it to be a welcoming space.

Creator: Miles Pennington / UTokyo DLX Design Lab

Location: Hatagaya

At the UTokyo DLX Design Lab, we aim to fuse design and engineering, and provide prototypes of innovative goods and services in collaboration with various specialists from Japan and overseas.

The Hatagaya public toilet grew out of research into design-led innovation by my team. We collected ideas by holding workshops with participants of various nationalities, ages, and genders, and then collaborated with architectural specialists to give shape to those ideas. Another special feature of the design process for the Hatagaya public toilet was that it included multiple discussions with local residents.

The main feature of this project is that we incorporated a “second space” with different functions from those of a public toilet. This second space is a plain, square shape that can be used for various purposes by anyone, regardless of age or gender. By functioning as an exhibition space and information center, we hope that it will play a useful role as the center of the local community.

To make this second space more usable, we included an original bench using 31 poles that can be raised or lowered to change its shape. In addition to a bench to sit on while waiting for someone, we hope that it will serve other uses for the local community by changing the formation according to the various ways it is used.

The toilet stalls are laid out on the three remaining triangular spaces. The space is limited, but I believe the high, slanted ceiling makes it feel larger than the actual floor space.

Designer: Junko Kobayashi

Location: Sasazuka Greenway

The location, near Sasazuka Station on the Keio train line, had restrictions in terms of construction methods and loads because of the pillars that are anchored into the ground to support the railway that runs overhead, and a water main that runs along the south side of the site. The material used for the structure is called COR-TEN steel, and I chose these highly durable steel panels because they can be assembled without cranes or heavy machinery and reduce the weight of the structure.

The materials and structure were chosen because of these restrictions, but the steel panels also have the advantage of being able to shape into curves. I didn’t start out with this exact shape in mind, however. I started with a flat plan with a universal toilet in the middle, a men’s and women’s toilet on each side, and a booth for children that is next to the sidewalk for easy access, and when we started to assemble the panels according to that plan, a cute shape began to emerge that looked like it came from a fairy tale.

Because it is a toilet, ease of use and safety are the top priorities, and in addition one of the design techniques we used was to place a large, round eave above the structures as a “second sky” to alleviate the sense of pressure from the railway running overhead. People have said the yellow color makes it look like the moon, and there are also rabbits looking out from the round windows, making this a cute “rabbit and moon” toilet. The rabbit illustrations were done by the graphic designer Tetsuya Ota. The sidewalk next to the facility is part of a walking course used by a local preschool, and I hope the children will enjoy using the toilet.

I have been involved with toilet design for many years, and I believe the true merits of a public toilet emerge after 30 or 40 years. We purposely exposed the COR-TEN steel panels to rust so that they will remain durable for many years, while also developing an attractive deeper, darker color over the years. As time passes, it will increasingly blend into its surroundings.

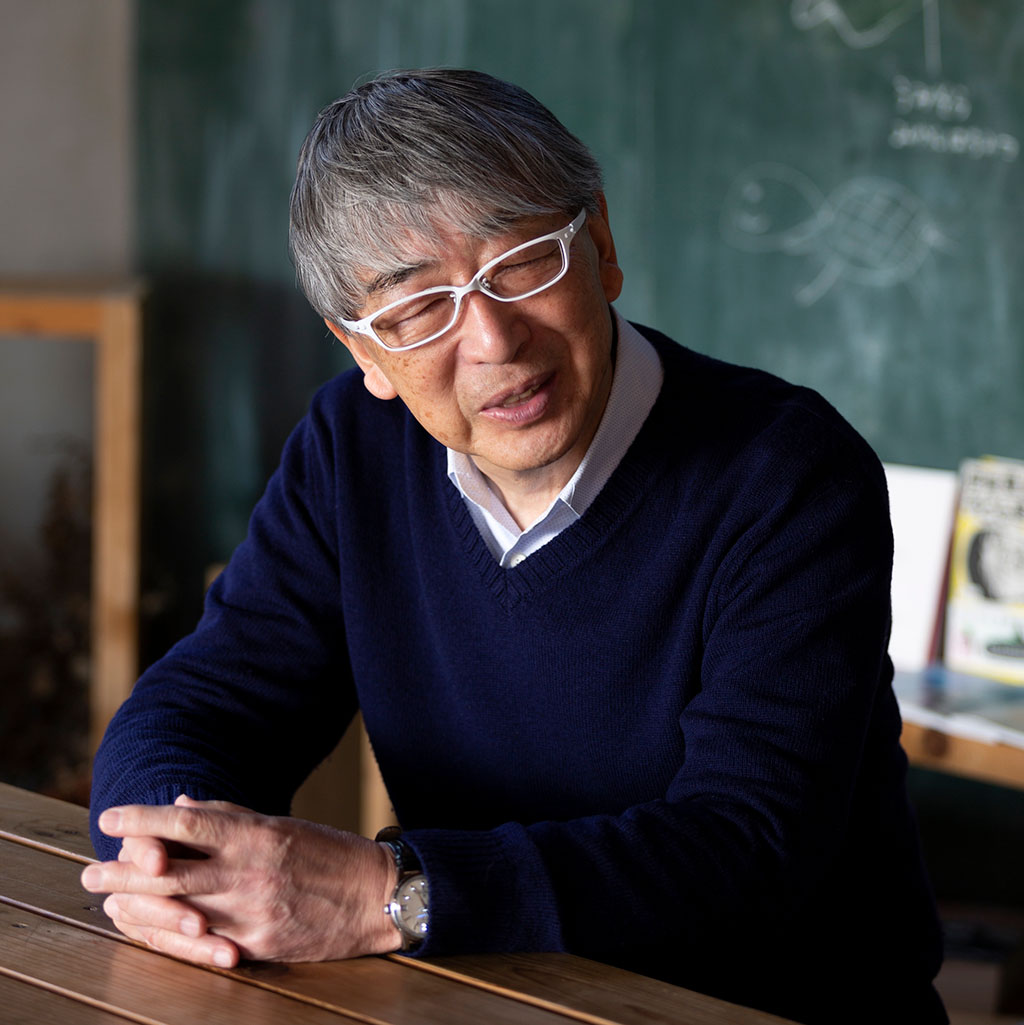

Designer: Sou Fujimoto

Location: Nishisando

The structure for a public toilet is small, which also limits its functions. The process of highlighting new possibilities was very interesting, but also involved difficulties. I wanted to create a toilet that was a new kind of public space that has “community value.” With that in mind, we thought about the relationship between the toilet and the community from a variety of angles, and after several years we arrived at the concept of Utsuwa – Izumi (Vessel – Spring).

In Japanese architectural terminology, a toilet is one of the areas referred to as mizu-mawari (an area where water circulates). Water is also symbolic of the natural environment and circulation. I thought that by thinking about a toilet as “a place with water,” it would be possible to bring out functions and attractiveness in ways that differed from conventional public toilets.

People in European cities are fond of public squares that have fountains. People become more aware of a space if it has water, and tend to gather there to engage in casual conversation. The coronavirus pandemic made people more conscious about washing their hands, and this also may have made me think again about the importance of a space with water. There is a sink for washing your hands inside each stall, but apart from those, there is also a space within the facility along the sidewalk with five faucets at different heights that give people access to fresh water, and everyone from wheelchair users and children to tall adults can use the one that suits them.

The toilet functions are the same as prior to the renovation, with two women’s stalls and one men’s stall and three urinals, and we added one barrier-free toilet. Nevertheless, I think it feels more spacious than the previous facility, with the overall facility, or “vessel,” opening toward the sidewalk. We also designed the approach so that you can see people coming and going and you can walk through with a sense of security, feeling that the structure is protecting you.